"You," he said to one boy, "are Ibo." "You are Hausa," to another. Soon, it was my turn. I took my place in front of him. He studied me, then leaned forward and smiled.

"You," he said, "are Fulani."

We all giggled; these words sounded so strange to our young ears.

"Come," he said. I followed him over to a giant shelf. He retrieved a book, opened it, pointed to a picture of a girl. "There. You see?"

I stared at it. And wondered how a picture of ten-year old me somehow got in this book Ishtu's wise relative was now holding. It was the first moment I actually seemed to make the real connection that somewhere, at some point in time, my relatives where there, before they were here. That my lineage stretched all the way back, back over and across the Atlantic, to another continent. It seemed to me a distant, magical place.

***********

Where are you from? It's a question most black Americans have the short answer to: We rattle off our birthplace, the city and state we were raised, where our relatives migrated from and to. Usually within the confines of the States, sometimes, the West Indies. Not many of us can say (with a degree of certainty) that our people were originally from the Congo, or Liberia, or South Africa.

"You definitely come from the East," we'd hear (constantly), from those folks familiar with people on the continent. As I got older, people began to ask the same of me. Depending on how I was rocking my hair at any given moment, people would guess, Trinidad, maybe? Ethiopia, Indian (dots, not feathers)? "Nah, I'm authentic black girl. From the States," I'd assure them. But it bugged me that I didn't have more to offer. "Someone once told me I looked Fulani," was my usual reply.

"Yes, I can see that. Strong possibility. They have a very distinct look, you know," my once Nigerian love, Yinka, would often co-sign. "A Yankee girl Fulani," he'd tease. "Well. One can only guess."

Around the same time, my mom (an avid traveler) had booked an educational trip to Egypt, but was forced to cancel. The wicked breast cancer had returned, for what would be, the last time. It began to quickly spread though her body; she became too sick to travel. Less than a year later, mommy was gone.

I promised myself two things. One - I would make that trip to Egypt for her, in her honor. (which is why Dr. Smith's suggestion a few weeks back is personally significant.) Two - I would pick up where her genealogical dig had left off. Except, I wanted to now explore a different route. I wanted to start from the beginning.

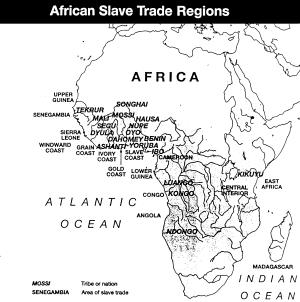

Soon enough, I'd come across information about Dr. Kittles, a biologist and co-director of Molecular Genetics at the National Human Genome Center at Howard University. He started an organization, African Ancestry, which through his research, has allowed him to compile an African Lineage Database (ALD) which contains 11,747 paternal lineages and 13,690 maternal lineages from over 160 ethnic groups across the African Continent. The ALD contains DNA sequence data from individuals throughout the continent of Africa, and there is a specific concentration on regions that are known to have participated in the TransAtlantic Slave Trade.

I did my research, and felt comfortable enough to pay the fee and request a kit. Then came the consent form, the cheek swabs, and off it all went, back to the lab. The rest..well, the rest is MY history.

Weeks later when that package finally arrived at my door, I sat and stared at it. Had a few glasses of wine over it, while quietly contemplating. What would be revealed? What if my DNA type couldn't be matched? (this is a possibility, Dr. Kittles warns, although slight) What if I'm not from Africa??? (don't laugh, it can happen). What if, what if....

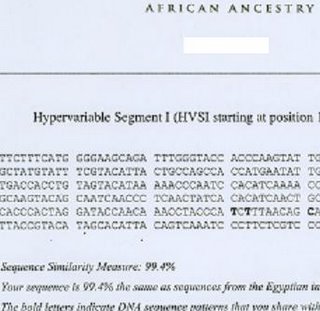

I finally woman-ed up; opened the package. The results? Well, it was a 99.4% match. And it said: Look to the east, black woman. Look to the east...

This is part of my report, my actual DNA sequence, and how my type was matched.

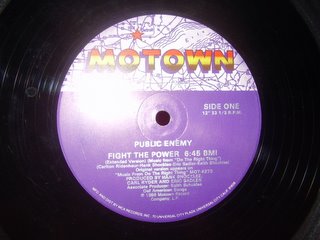

After years of study, I'd also learned that the Fulani were one of the most widely known group of nomads in Africa, who presently, live in communities throughout much of West Africa, from Senegal to Cameroon and as far east as Sudan and Ethiopia. It is also said that slavery and colonialism dispersed Fulani throughout the Middle East, the Americas and Europe. American history books are full of individuals of Fulani origin who have distinguished themselves in North and South America and the Caribbean.

So, perhaps that wise man from Cameroon wasn't too far off, after all.

My black history project has been such a wonderful instrument on my journey toward self. It's not the entire picture, but it gives me a valuable piece to integrate into my cultural autobiography. As a result, when I look in the mirror - now, I see so much more. Yes, I'm still the thick-haired, round the way girl who came up in Inglewood, by way of Ohio, by way of a Virginia plantation - AND, I'm a Nubian sista in the New World, distant daughter of Isis, descendant of the most original people on Earth. I now watch my daughter compose her black history reports with pride; for she now has two places, on two maps, she can point to.

In regard to the reparations argument for African descendants in America, I now think this is something that should be included in the prospective package: A DNA test should be offered to any black person in America who wishes to trace his or her roots. Considering our forced migration, I think this would be a positive form of restitution; a unique way to allow us to reinstate the missing parts of our past.

Until then - we can choose to start down the path on our own. For more information on how to start on your individual Black History project, visit these links:

African Ancestry

African American Lives PBS special hosted by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Ancestry by DNA

Roots for Real

Motherland: A Genetic Journey (program on BBC)

Be sure to check out these bloggers who have mentioned their journeys:

DNA Can Set You Free at OTV.

Tracing Our Roots at Emerging Phoenix

My DNA at Mz. Powderpink's

Happy Black History! It's not just for a month. It's fo' life.